Image File Formats Responsive Web Design Software

Responsive web design software is the first step to creating a website that can adapt to different devices and screen sizes. The software allows designers to create one site for multiple platforms, so they can create a single URL for desktop, mobile and tablet.

Table of Contents

Image File Formats Responsive Web Design Software

Responsive images that are in the wrong format, images that are not compressed properly, and images that are too big will all decrease the page speed and impact your SEO.

According to Google, anything above 2 seconds of download time will put off your users and discourage the crawlers from indexing your website.

I learned that the hard way when I was rebuilding my website. My goal was to create a simple website that downloads in the blink of an eye. To do so, I went for Gatsby.js — it’s fast and I know it.

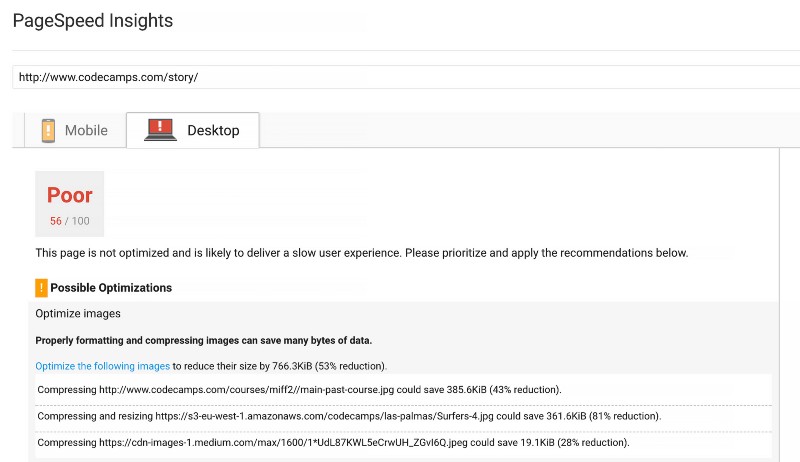

After a few days of coding, the website was up and running. But, to my disappointment, it scored a modest 78/100 on mobile and a disastrous 57/100 on the desktop on PageSpeed Insights. Not good at all.

PageSpeed Insights suggested an easy fix to the problem. Just download the compressed images the tool has created, and you’ll be fine.

That sparked my curiosity. And the more I thought about sizes, formats, and compression levels, the more I felt overwhelmed with the abundance of choices. PNGs, JPGs, SVGs, inline base64 encoded strings… or maybe WebPs?

To wrap my head around it, I dived into the world of pixels, waded through the muddy waters of random tips on the subject, and came up with a systematic approach.

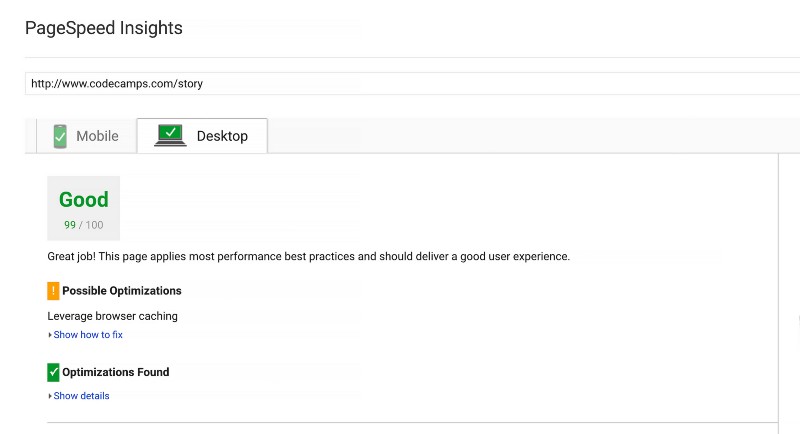

And once I applied what I learned, my PageSpeed rating increased from 78 to 91 on mobile and from 57 to 99 on desktop!

In this post, I will show you how to quickly generate responsive images that work in all browsers and massively reduce your download speeds.

Before you start

If you want to optimize an image, you have to start with a high-quality image that has the right format and the right size:

- Use JPGs for photos and PNGs for graphics or other images that require transparency

- Use smaller PNG-8 instead of PNG-24 for graphics with a limited number of colors. To decrease the size even further, you can also reduce the number of colors, from 256 to 16

- Use SVGs (vector graphic images) for icons and logos. They will scale nicely without increasing the size of your file

- Use inline images below 10KB as 64base encoded strings (sparingly)

- The actual width of an image shouldn’t exceed the width of the largest container it will be displayed in, multiplied by two (for retina displays)

Hardware and software pixels

The image that takes the full width of the 15″ Macbook Pro screen is 1440 pixels wide but the actual resolution of the retina display is double that, at 2880×1800. Why? Because of its pixel density factor of 2.

Old monitors have a pixel density of 1. But since screen resolutions have increased in recent years, the hardware pixel is no longer equal to the software or CSS pixel.

The relationship between hardware and CSS pixels is described by the following formula:

CSS Pixels = Hardware Pixels / Pixel density

Therefore, hardware resolution of 2880 pixels translates to1440 CSS pixels on the retina display. This also explains why, when you inspect the full-width image in Developer Tools, you will see it as only 1440 pixels wide instead of the original 2880 pixels.

The retina display was a major breakthrough a few years ago. Today, mobile devices have even “denser” displays of 3 and even 4 for Samsung Galaxy S8+!

For the purpose of my experiment, I decided that to be razor-sharp, the full-width image should have the maximum width of 2880 pixels.

With the image height set to 600px and the quality to 75%, Photoshop produced a massive 939KB file. That’s hardly acceptable.

After a few experiments with compression levels, it became clear that compressing JPGs below 60% quality resulted in a visible loss of quality. I set the quality to 60% as a starting point and the image size dropped to 681KB. Still, far from decent.

WebP format

“WebP is a modern image format that provides superior lossless and lossy compression for images on the web,” according to Google.

After conversion to the WebP format, my image was not only smaller but also

sharper! WebP shaved another 34% of the compressed JPEG size. “I’m on the right path”, I thought!

Unfortunately, the WebP format is supported by Chrome and Opera, just about 60% of all browsers, according to Can I use. So I knew I’d have to think of fallback options.

At last, the limits were set:

- 60% compression level

- WebP format where possible

I also chose to support three breakpoints: 600px and 900px

(here is why) and 2-pixel densities — 1x and 2x for retina displays. That meant 6 different images instead of just two. Supporting the WebP format doubled the number.

There are two primary ways to put an image on a website, either by using HTML’s img element or a background-image in CSS.

Responsive images in HTML

The basic HTML img element has the src attribute that points to the image URL:

<img src="image.jpg" alt="image description"/>But you can go a step further and decide which image to serve depending on the screen’s pixel density with the srcset attribute:

<img srcset="image_1x.jpg 1x, image_2x.jpg 2x" src="image_1x.jpg"/>Here, I’ve used two different screen densities: 1x and 2x. Depending on the actual display density, the browser will choose the right one. The src attribute points to the fallback option.

At the moment, most browsers except IE, Edge, and Opera Mini have the srcset attribute implemented.

This solution seems like a step in the right direction. Unfortunately, your browser will always select the same image, with the same pixel density, regardless of the display size. And the same image will end up on both the desktop and the mobile device.

We need more control. And we can have it. Apart from pixel densities, the scrset attribute accepts width units w, an equivalent of CSS pixels.

The width unit enables the browser to choose the right image size for the given display capabilities.

With two breakpoints (600px and 900px), we can go with three different image sizes:

<img

srcset="image-sm.jpg 600w,

image-md.jpg 900w,

image-lg.jpg 1440w"

src="image_1x.jpg"

/>

There is a caveat here. When the browser decides which image to fetch, it has no knowledge of our CSS! The CSS file hasn’t been fetched at this point. And it assumes that the image will be displayed at the full width of the window.

If a full-width image is what you want, then fine. But what if you want to place an image in a container that is only 50vw wide? Here comes the sizes attribute into play. Let’s take a look:

<img

srcset="image-sm.jpg 600w,

image-md.jpg 900w,

image-lg.jpg 1440w"

sizes="50vw"

src="image_1x.jpg"

/>

By adding the sizes="50vw" attribute, you are telling the browser that the image will be displayed at 50vw, and based on this information, the browser will decide which image to display.

But what if you want to display your image at 50vw on a big screen and at the full width of 100vw on a mobile device? The sizes attribute accepts also media queries!

You can specify that below the mobile breakpoint of 600px you want the browser to display your image at a full-screen width. And for the width higher than the mobile breakpoint you want the browser to display your image at 50vw.

You can do this by adding the media query:

<img

srcset="image-sm.jpg 600w,

image-md.jpg 900w,

image-lg.jpg 1440w"

sizes="(max-width: 600px) 100vw, 50vw"

src="image_1x.jpg"

/>

Remember that in the above line of code you are instructing the browser which image to choose because the browser doesn’t know the corresponding CSS. You still have to add the breakpoints in CSS explicitly.

This solution works really well but we are missing pixel densities here! If we stopped here, we would be sending the same image both to the displays with 1x pixel density and to the retina screens. Luckily, there is an easy fix to it.

Picture element

Meet the HTML5 picture element. It accepts the source and img elements as its children. We can use the source element to list additional image formats that we want to serve to the browser.

But before we fix pixel densities, let’s introduce smaller and sharper images in WebP format.

Let’s add the source element as the first option inside the picture element with your image in the WebP format followed by the img pointing at the regular JPG image. Now, when the browser is not WebP-ready, it will gracefully fall back on to the img element (e.g. Safari).

<picture>

<source

srcset="image.webp"

type="image/webp"

/>

<img

src="image.jpg"

type="image/jpeg"

alt="image description"

/>

</picture>

The source element opens up a whole new world of possibilities. It accepts media queries!

First, in the media attribute, we use the media query and then, in the srcsetattribute, we place the appropriate image. And we can use as many sourceelements as we wish:

<picture>

<source

media="(min-width: 900px)"

srcset="image-lg.webp"

type="image/webp"

/>

<source

media="(min-width: 600px)"

srcset="image-md.webp"

type="image/webp"

/>

<source

srcset="image-sm.webp"

type="image/webp"

/>

<img

src="image-lg.jpg"

type="image/jpeg"

alt="image description"

/>

</picture>

Above, we have prepared three images in the WebP format, depending on the size of the display, and one JPG image as a fallback option.

The last secret of the srcset attribute is that it also accepts pixel densities. We can decide which image we want to serve on which screen and at which pixel density. The trick is to list image files in the scrset followed by a space and the pixel density factor, for example: 1x, 2x, 3x, or even 4x.

<picture>

<source

media="(min-width: 900px)"

srcset="image-lg_1x.webp 1x, image-lg_2x.webp 2x"

type="image/webp" />

<source

media="(min-width: 601px)"

srcset="image-md_1x.webp 1x, image-md_2x.webp 2x"

type="image/webp" />

<source srcset="image-sm_1x.webp 1x, image-sm_2x.webp 2x" type="image/webp" />

<img

srcset="image-sm_1x.jpg 600w, image-md_1x.jpg 900w, image-lg_1x.jpg 1440w"

src="image_lg_1x.jpg"

type="image/jpeg"

alt="image description"

/>

</picture>

...Since we sorted out the screen sizes and pixel densities for the WebP format, let’s have a closer look at the fallback option. In the end, some browsers don’t support the WebP format.

Here, we have to decide if we want to use the 1 or 2-pixel-dense images. Below, I went for the first option:

<picture>

<source

media="(min-width: 900px)"

srcset="image-lg_1x.webp 1x, image-lg_2x.webp 2x"

type="image/webp"

/>

<source

media="(min-width: 601px)"

srcset="image-md_1x.webp 1x, image-md_2x.webp 2x"

type="image/webp"

/>

<source srcset="image-sm_1x.webp 1x, image-sm_2x.webp 2x" type="image/webp" />

<img

srcset="image-sm_1x.jpg 600w, image-md_1x.jpg 900w, image-lg_1x.jpg 1440w"

src="image_lg_1x.jpg"

type="image/jpeg"

alt="image description"

/>

</picture>

We have replaced the img element with the picture element. Where possible, we want to deliver images in the WebP format in three different sizes, depending on the display size, and 2 different pixel densities. If the browser doesn’t support the picture element or the WebP format, it will fall back on to the standard img element with three different sizes of JPGs.

Important: Notice that in the img element the srcset attribute should be placed before the src attribute. Otherwise, the browser will download the src image first and then, if it finds a better image in the srcset, it will download this one as well. This way we would end up with two images.

We could go one step further and create another 3 source elements for browsers that don’t support the WebP format and deliver JPG files instead.

Although it works great for Firefox, I’ve noticed that Safari will download both files: the JPG listed in the source and the JPG from the img element. Again, we would end up with two images instead of one.

Responsive images in CSS

If we don’t know the exact height and width of the container we want to cover with an image, we can use generic elements like div with the background-imageproperty pointing to the image URL:

background-image: url("/images/image.jpg");CSS, similarly to HTML, enables image size optimization.

The image-set in CSS is the equivalent of the srcset in HTML . At the moment, it is implemented in Chrome, Chrome for Android, Safari, iOS Safari, and a few other browsers. You can add polyfills to make the image-setwork on other browsers, but given that Chrome and Safari combined are the browsers of choice for 70% of users today, there is a good chance that most browsers will implement the attribute in the near future.

But worry not, the regular background-image as a fallback option will do the trick.

The structure is very similar to what we’ve just used in a srcset attribute.

To create a full-width image element with a height of 500px, we have to start with the fallback option — the first background-image in the code example below. Then, using the -webkit-image-set, we need to list the WebP images for different pixel densities. And we have to repeat the process for different breakpoints using media queries.

One important thing to remember is that both Chrome and Safari use the WebKit layout engine but Safari doesn’t support the WebP format. That’s why we have to add the last set of image-set attributes with JPG images (it will be used by Safari even though it doesn’t start with -webkit).

.bg-image {

width: 100vw;

height: 500px;

background-size: cover;

background-position: center;

background-image: url(/images/image-lg_1x.jpg);

background-image: -webkit-image-set(

url(/images/image-lg_1x.webp) 1x,

url(/images/image-lg_2x.webp) 2x

);

background-image: image-set(

url(/images/image-lg_1x.jpg) 1x,

url(/images/image-lg_2x.jpg) 2x

);

@media (max-width: 900px) {

background-image: url(/images/image-md_2x.jpg);

background-image: -webkit-image-set(

url(/images/image-md_1x.webp) 1x,

url(/images/image-md_2x.webp) 2x

);

background-image: image-set(

url(/images/image-md_1x.jpg) 1x,

url(/images/image-md_2x.jpg) 2x

);

}

@media (max-width: 600px) {

background-image: url(/images/image-sm_2x.jpg);

background-image: -webkit-image-set(

url(/images/image-sm_1x.webp) 1x,

url(/images/image-sm_2x.webp) 2x

);

background-image: image-set(

url(/images/image-sm_1x.jpg) 1x,

url(/images/image-sm_2x.jpg) 2x

);

}

}

Here, the background image is centered in the div element and covers its whole area. Using the image-set attribute, we are assigning two different images to two different pixel densities.

The fallback option with a standard url takes care of the browsers that don’t support the image-set attribute.

It’s very important to place the fallback option before the background-imageswith the image-set attribute. If you place it after the image-setattribute, for example, Safari would download both, the image from image-set and the image from the fallback option if it found an image with a different file name.

The rest of the code follows the same pattern. Above, I have added media queries for 600px and 900px breakpoints and a set of corresponding images in smaller sizes.

The fallback option always has to use the JPG format to avoid the situation where an image cannot be shown at all, that is when the browser doesn’t support the image-set attribute or the WebP format.

How to inline small images

To improve user experience, we should not only compress and serve the smallest possible images, but we should also decrease the number of requests we send to the server.

The browser has to send a separate request for every single image. When sent to the server, the request has to first wait in a queue, which takes time. The more calls the browser makes, the longer the user has to wait.

That’s especially true when you have to download many small images. If possible, logos and icons should be saved as vector graphics (SVG). Small images can be embedded either in HTML or in CSS directly as base64 encoded strings.

Instead of passing a regular URL to the src attribute in the img element, we can pass the image as a string:

<img

src="data:image/png;base64,encoded string"

alt="img description"

/>and in CSS:

.small-image {

background-image: url(data:image/png;base64,encoded string);

}

In most cases, the generated string will be around 30% bigger than the original image, but you will save time on another round trip to the server.

The most common argument against using base64 encoded images in CSS files is that images are non-blocking resources whereas CSS files are. It means that if you embed too many small images into your CSS, it will increase the size of the CSS file and lengthen the time to the first paint of the website. That, in turn, will make the user wait longer before he or she can see any content.

Here is a great article on why you may consider dropping the idea of using encoded strings for images entirely.

The truth lays probably somewhere in the middle, and injecting one or two small files as base64 strings into CSS or HTML shouldn’t do any harm.

At the end of this article, you will learn how to generate them. It can feel strange at first because these strings are thousands of characters long. Your .logo class may look like this, but longer:

.logo {

background-image: url(data:image/png;base64,iVBORw0KGgoAAAA NSUhEUgAABqIAAAFvCAMAAAAWmCq0AAAAGXRFWHRTb2Z0d2FyZQBBZG9iZS BJbWFnZVJlYWR5ccllPAAAA3hpVFh0WE1MOmNvbS5hZG9iZS54bXAAAAAAA Dw/eHBhY2tldCBiZWdpbj0i77u/IiBpZD0iVzVNME1wQ2VoaUh6cmVTek5U Y3prYzlkIj8+IDx4OnhtcG1ldGEgeG1sbnM6eD0iYWRvYmU6bnM6bWV0…);

}

How to generate responsive images

Let’s assume that you’ve just saved a perfect image and you’d like to create all the variations so you can use it on your website.

There are many tools that can help. Simple tools include compressjpeg.com, compresspng.com, and tinyjpg.com. More advanced tools include ImageOptim for JPEG, PNGs, and GIFs and ImageAlpha for PNGs.

On my quest to take full control of compression levels, formats, and scaling, I needed a tool that would help me automate the whole process. And I didn’t fancy drag-and-dropping dozens of images.

Both ImageMagic and GraphicsMagick are free and powerful pieces of software that painlessly pair with Grunt, the JavaScript task runner.

Even better, there are Grunt plugins that simplify the task further. Several quick tests showed that GraphicsMagick generates 20% smaller JPG images than ImageMagic at the same compression level. So the choice was clear.

Before we start to cut our way through the jungle of pixels, we have to prepare our tools and sharpen our axe. Download GraphicsMagick from here or use Homebrew to install it.

brew install graphicsmagickNext, install Grunt’s CLI globally:

npm install -g grunt-cliCreate a separate folder responsive-images and init the project:

mkdir responsive-images

cd responsive-images

npm initAnd finally, install the local version of Grunt:

npm install grunt --save-devCreate two folders: src/ for original images and dest/ for the responsive images that Grunt and GraphicsMagick will generate:

mkdir srcmk

dir destThe original image should be saved at the resolution equal to or greater than the largest image you want to generate in the src/ folder. I saved mine as JPG at 100% quality and 2880 pixels wide. It was around 2.5MB.

First, let’s generate responsive images using the grunt-responsive-imagesplugin. Install it:

npm install grunt-responsive-images --save-devNow, in the root directory of the project, create an additional file Gruntfile.js:

touch Gruntfile.jsThis is where we have to configure the plugin.

Copy and paste the code to the Gruntfile.js and let me walk you through the code:

module.exports = function (grunt) {

grunt.initConfig({

responsive_images: {

dev: {

options: {

engine: "gm",

sizes: [

{ name: "sm", suffix: "_1x", quality: 60, width: 600 },

{ name: "sm", suffix: "_2x", quality: 60, width: 1200 },

{ name: "md", suffix: "_1x", quality: 60, width: 900 },

{ name: "md", suffix: "_2x", quality: 60, width: 1800 },

{ name: "lg", suffix: "_1x", quality: 60, width: 1440 },

{ name: "lg", suffix: "_2x", quality: 60, width: 2880 },

],

},

files: [

{

expand: true,

src: ["**/*.{jpg,png}"],

cwd: "src/",

dest: "dest/",

},

],

},

},

});

grunt.loadNpmTasks("grunt-responsive-images");

grunt.registerTask("default", ["responsive_images"]);

};

In options, we set GraphicsMagick as our engine of choice: engine: "gm". You can also test ImageMagick by changing it to engine: "im".

Next, in the sizes array, we have to specify the parameters of the images we want to produce, such as a name that will be appended to the original name, a suffix that will be added to the name as well, a quality and a width.

The resulting images will have the following naming structure:

original-[name]_[suffix}.jpgFor example, using the first sizes object, Grunt will generate from the original my-image.jpg the my-image-sm_1x.jpg image at 60% compression level and 600 pixels wide.

Below the options, we need to list source and destination folders as well as patterns of file names that we want to process.

To enable the dynamic build of file objects, let’s set the expand attribute to true and define:

cwd— source foldersrc— an array of patterns to match. In our case, we want to match any folder (**) inside the source folder and all files with extensionsjpgorpngdest— destination folder

The above Grunt task will generate a set of JPG and/or PNG files, depending on the source image file extensions.

We also want to produce a corresponding set of WebP images.

We need another plugin to do the job: grunt-cwebp. Let’s install it:

npm install grunt-cwebp --save-devAppend the Gruntfile.js with the following configuration:

module.exports = function (grunt) {

grunt.initConfig({

responsive_images: {

...

},

cwebp: {

dynamic: {

options: {

q: 60,

},

files: [

{

expand: true,

cwd: "dest/",

src: ["**/*.{jpg,png}"],

dest: "dest/",

},

],

},

},

});

grunt.loadNpmTasks("grunt-responsive-images");

grunt.loadNpmTasks("grunt-cwebp");

grunt.registerTask("default", ["responsive_images", "cwebp"]);

};

The grunt-cwebp plugin uses the dest/ folder as the source of images. We want all the newly produced JPGs to have their WebP siblings and we should place them in the same folder.

Now, we can process the images:

gruntFor every image in the src/ folder, Grunt will generate 12 images in all the necessary sizes, pixel densities and in both JPG and WebP format!

How to generate base64 strings

If you want to generate base64 strings for inlining your images, here is how to do.

This time, let’s use the Grunt plugin: grunt-base64.

Create a new project in a separate folder base64-images. Init it with npm and install the local version of Grunt:

mkdir base64-images

cd base64-images

npm init

npm install grunt --save-devInstall the grunt-base64 plugin:

npm install grunt-base64 --save-devIn the root directory, create a new images/ folder and the Gruntfile.js:

mkdir images

touch Gruntfile.jsand copy and paste the code into the Gruntfile.js:

module.exports = function (grunt) {

grunt.initConfig({

base64: {

dev: {

files: {

"images/output.b64": ["images/*.{jpg,png}"],

},

},

},

});

grunt.loadNpmTasks("grunt-base64");

grunt.registerTask("default", ["base64"]);

};

Place the small original image in the images/ folder and run Grunt:

gruntAfter the task is finished, copy the whole content from the output.b64 file — that’s the base64 string that you can paste into the url of the background-image or into the src attribute of the img element.

There is also an easier way (on Mac OS X or Linux):

uuencode -m image-file-name remotenameThe remotename is not used and you can place even xyz to get base64 string printed into the standard output — in most cases into the terminal window.

You have to use -m option to get the base64 encoding.

Conclusion

Responsive images might feel overwhelming at first, but with Grunt and image processing engines on your side, you can create a smooth process and automate most of the repetitive tasks. And I promise it’s worth it. You will not only shine in PageSpeed Insights, but you will also slash the time to the first paint of your website.

In my case, the original 939KB image shrank by 60% to 380KB (JPG) and by 77% to 218KB in the WebP format.

In the end, my pixel-crusade paid off — the PageSpeed Insight rating for my website turned green.

If you liked this article, 👏 even 50 times — I would really appreciate it and it makes a huge difference to me.

responsive images

This guide is about the HTML syntax for responsive images (and a little bit of CSS for good measure). The responsive images syntax is about serving one image from multiple options based on rules and circumstances. There are two forms of responsive images, and they’re for two different things:

If your only goal is…

Increased Performance

Then what you need is…

<img

srcset=""

src=""

alt=""

>There is a lot of performance gain to be had by using responsive images. Image weight has a huge impact on pages’ overall performance, and responsive images are one of the best things that you can do to cut image weight. Imagine the browser being able to choose between a 300×300 image or a 600×600. If the browser only needs the 300×300, that’s potentially a 4× bytes-over-the-wire savings! Savings generally go up as the display resolution and viewport size go down; on the smallest screens, a couple of case studies have shown byte savings of 70–90%.JUMP TO USING SRCSET

If you also need…

Design Control

Then what you need is…

<picture>

<source srcset="" media="">

<source srcset="" media="">

<img src="" alt="">

</picture>Another perfectly legit goal with responsive images is not just to serve different sizes of the same image, but to serve different images. For example, cropping an image differently depending on the size of the screen and differences in the layout. This is referred to as “art direction.”

The <picture> element is also used for fallback image types and any other sort of media query switching (e.g. different images for dark mode). You get greater control of what browsers display.JUMP TO USING <PICTURE>

There is a lot to talk about here, so let’s go through both syntaxes, all of the related attributes and values, and talk about a few related subjects along the way, like tooling and browsers.

Using srcset

The <img srcset="" src="" alt=""> syntax is for serving differently-sized versions of the same image. You could try to serve entirely different images using this syntax, but browsers assume that everything in a srcset is visually-identical and will choose whichever size they think is best, in impossible-for-you-to-predict ways. So I wouldn’t reccomend it.

Perhaps the easiest-possible responsive images syntax is adding a srcset attribute with x descriptors on the images to label them for use on displays with different pixel-densities.

<img

alt="A baby smiling with a yellow headband."

src="baby-lowres.jpg"

srcset="baby-highres.jpg 2x"

>

Here, we’ve made the default (the src) the “low res” (1×) copy of the image. Defaulting to the smallest/fastest resources is usually the smart choice. We also provide a 2× version. If the browser knows it is on a higher pixel-density display (the 2x part), it will use that image instead.

<img

alt="A baby smiling with a yellow headband."

src="baby-lowres.jpg"

srcset="

baby-high-1.jpg 1.5x,

baby-high-2.jpg 2x,

baby-high-3.jpg 3x,

baby-high-4.jpg 4x,

baby-high-5.jpg 100x

"

>You can do as many pixel-density variants as you like.

While this is cool and useful, x descriptors only account for a small percentage of responsive images usage. Why? They only let browsers adapt based on one thing: display pixel-density. A lot of times, though, our responsive images are on responsive layouts, and the image’s layout size is shrinking and stretching right along with the viewport. In those situations, the browser needs to make decisions based on two things: the pixel-density of the screen, and the layout size of the image. That’s where w descriptors and the sizes attribute come in, which we’ll look at in the next section.

Using srcset / w + sizes

This is the good stuff. This accounts for around 85% of responsive images usage on the web. We’re still serving the same image at multiple sizes, only we’re giving the browser more information so that it can adapt based on both pixel-density and layout size.

<img

alt="A baby smiling with a yellow headband."

srcset="

baby-s.jpg 300w,

baby-m.jpg 600w,

baby-l.jpg 1200w,

baby-xl.jpg 2000w

"

sizes="70vmin"

>We’re still providing multiple copies of the same image and letting the browser pick the most appropriate one. But instead of labeling them with a pixel density (x) we’re labelling them with their resource width, using w descriptors. So if baby-s.jpg is 300×450, we label it as 300w.

Using srcset with width (w) descriptors like this means that it will need to be paired with the sizes attribute so that the browser will know how large of a space the image will be displaying in. Without this information, browsers can’t make smart choices.

Creating accurate sizes

Creating sizes attributes can get tricky. The sizes attribute describes the width that the image will display within the layout of your specific site, meaning it is closely tied to your CSS. The width that images render at is layout-dependent rather than just viewport dependent!

Let’s take a look at a fairly simple layout with three breakpoints. Here’s a video demonstrating this:Demo

The breakpoints are expressed with media queries in CSS:

body {

margin: 2rem;

font: 500 125% system-ui, sans-serif;

}

.page-wrap {

display: grid;

gap: 1rem;

grid-template-columns: 1fr 200px;

grid-template-areas:

"header header"

"main aside"

"footer footer";

}

@media (max-width: 700px) {

.page-wrap {

grid-template-columns: 100%;

grid-template-areas:

"header"

"main"

"aside"

"footer";

}

}

@media (max-width: 500px) {

body {

margin: 0;

}

}The image is sized differently at each breakpoint. Here’s a breakdown of all of the bits and pieces that affect the image’s layout width at the largest breakpoint (when the viewport is wider than 700px):

100vw minus all that explicitly sized margin, padding, column widths, and gap.- At the largest size: there is 9rem of explicit spacing, so the image is

calc(100vw - 9rem - 200px)wide. If that column used afrunit instead of200px, we’d kinda be screwed here. - At the medium size: the sidebar is dropped below, so there is less spacing to consider. Still, we can do

calc(100vw - 6rem)to account for the margins and padding. - At the smallest size: the body margin is removed, so just

calc(100vw - 2rem)will do the trick.

Phew! To be honest, I found that a little challenging to think out, and made a bunch of mistakes as I was creating this. In the end, I had this:

<img

...

sizes="

(max-width: 500px) calc(100vw - 2rem),

(max-width: 700px) calc(100vw - 6rem),

calc(100vw - 9rem - 200px)

"

/>A sizes attribute that gives the browser the width of the image across all three breakpoints, factoring in the layout grid, and all of the surrounding gap, margin, and padding that end up impacting the image’s width.

Now wait! Drumroll! 🥁🥁🥁That’s still wrong. I don’t understand why exactly, because to me that looks like it 100% describes what is happening in the CSS layout. But it’s wrong because Martin Auswöger’s RespImageLint says so. Running that tool over the isolated demo reports no problems except the fact that the sizes attribute is wrong for some viewport sizes, and should be:

<img

...

sizes="

(min-width: 2420px) 2000px,

(min-width: 720px) calc(94.76vw - 274px),

(min-width: 520px) calc(100vw - 96px),

calc(100vw - 32px)

"

>I don’t know how that’s calculated and it’s entirely unmaintainable by hand, but, it’s accurate. Martin’s tool programmatically resizes the page a bunch and writes out a sizes attribute that describes the actual, observed width of the image over a wide range of viewport sizes. It’s computers, doing math, so it’s right. So, if you want a super-accurate sizes attribute, I’d recommend just putting a wrong one on at first, running this tool, and copying out the correct one.

For an even deeper dive into all this, check out Eric Portis’ w descriptors and sizes: Under the hood.

Being more chill about sizes

Another option is use the Horseshoes & Hand Grenades Method™ of sizes (or, in other words, close counts). This comes highly suggested.

For example, sizes="96vw" says, “This image is going to be pretty big on the page — almost the full width — but there will always be a little padding around the edges, so not quite. Or sizes="(min-width: 1000px) 33vw, 96vw" says, “This image is in a three-column layout on large screens and close to full-width otherwise.” Practicality-wise, this can be a sane solution.

You might find that some automated responsive image solutions, which have no way of knowing your layout, make a guess — something like sizes="(max-width: 1000px) 100vw, 1000px". This is just saying, “Hey we don’t really know much about this layout, but we’re gonna take a stab and say, worst case, the image is full-width, and let’s hope it never renders larger than 1000px”.

Abstracting sizes

I’m sure you can imagine how easy it is to not only get sizes wrong, but also have it become wrong over time as layouts change on your site. It may be smart for you to abstract it using a templating language or content filter so that you can change the value across all of your images more easily.

I’m essentially talking about setting a sizes value in a variable once, and using that variable in a bunch of different <img> elements across your site. Native HTML doesn’t offer that, but any back end language does; for instance, PHP constants, Rails config variables, the React context API used for a global state variable, or variables within a templating language like Liquid can all be used to abstract sizes.

<?php

// Somewhere global

$my_sizes = "";

?>

<img

srcset=""

src=""

alt=""

sizes="<?php echo $my_sizes; ?>"

/>“Browser’s choice”

Now that we have a sizes attribute in place, the browser knows what size (or close to it) the image will render at and can work its magic. That is, it can do some math that factors in the pixel density of the screen, and the size that the image will render at, then pick the most appropriately-sized image.

The math is fairly straightforward at first. Say you’re about to show an image that is 40vw wide on a viewport that is 1200px wide, on a 2x pixel-density screen. The perfect image would be 960 pixels wide, so the browser is going to look for the closest thing it’s got. The browser will always calculate a target size that it would prefer based on the viewport and pixel-density situations, and what it knows from sizes, and compare that target to what it’s got to pick from in srcset. How browsers do the picking, though, can get a little weird.

A browser might factor more things into this equation if it chooses to. For example, it could consider the user’s current network speeds, or whether or not the user has flipped on some sort of “data saver” preference. I’m not sure if any browsers actually do this sort of thing, but they are free to if they wish as that’s how the spec was written. What some browsers sometimes choose to do is pull from cache. If the math shows they should be using a 300px image, but they already have a 600px in local cache, they will just use that. Smart. Room for this sort of thing is a strength of the srcset/sizes syntax. It’s also why you always use different sizes of the same image, within srcset: you’ve got no way to know which image is going to be selected. It’s the browser’s choice.

This is weird. Doesn’t the browser already know this stuff?

You might be thinking, “Uhm why do I have to tell the browser how big the image will render, doesn’t it know that?” Well, it does, but only after it’s downloaded your HTML and CSS and laid everything out. The sizes attribute is about speed. It gives the browser enough information to make a smart choice as soon as it sees your <img>.

<img

data-sizes="auto"

data-srcset="

responsive-image1.jpg 300w,

responsive-image2.jpg 600w,

responsive-image3.jpg 900w"

class="lazyload"

/>Now you might be thinking, “But what about lazy-loaded images?” (as in, by the time a lazy-loaded image is requested, layout’s already been done and the browser already knows the image’s render size). Well, good thinking! Alexander Farkas’ lazysizes library writes out sizes attributes automatically on lazyload, and there’s an ongoing discussion about how to do auto-sizes for lazy-loaded images, natively.

sizes can be bigger than the viewport

Quick note on sizes. Say you have an effect on your site so that an image “zooms in” when it’s clicked. Maybe it expands to fill the whole viewport, or maybe it zooms even more, so that you can see more detail. In the past, we might have had to swap out the src on click in order to switch to a higher-res version. But now, assuming a higher-res source is already in the srcset, you can just change the sizes attribute to something huge, like 200vw or 300vw, and the browser should download the super-high-res source automatically for you. Here’s an article by Scott Jehl on this technique.

Using <picture>

Hopefully, we’ve beaten it into the ground that <img srcset="" sizes="" alt=""> is for serving differently-sized versions of the same image. The <picture> syntax can do that too, but the difference here is that the browser must respect the rules that you set. That’s useful when you want to change more than just the resolution of the loaded image to fit the user’s situation. This intentional changing of the image is usually called “art direction.”

Art Direction

<picture>

<source

srcset="baby-zoomed-out.jpg"

media="(min-width: 1000px)"

/>

<source

srcset="baby.jpg"

media="(min-width: 600px)"

/>

<img

src="baby-zoomed-in.jpg"

alt="Baby Sleeping"

/>

</picture>This code block is an example of what it might look like to have three stages of an “art directed” image.

- On large screens, show a zoomed-out photo.

- On medium screens, show that same photo, zoomed in a bit.

- On small screens, zoom in even more.

The browser must respect our media queries and will swap images at our exact breakpoints. That way, we can be absolutely sure that nobody on a small screen will see a tiny, zoomed-out image, which might not have the same impact as one of the zoomed-in versions.

Here’s a demo, written in Pug to abstract out some of the repetitive nature of <picture>.https://codepen.io/anon/embed/YzyKJpw?height=450&theme-id=1&slug-hash=YzyKJpw&default-tab=html,result

Art direction can do a lot more than just cropping

Although cropping and zooming like this is the most common form of art direction by far, you can do a lot more with it. For instance, you can:

- Dark-ify™ images for users in dark mode,

- avoid sending animated GIFs to users with a “prefers reduced motion” accessibility preference,

- re-arrange image content so that it all fits “above the fold” on short viewports,

- set a maximum resolution cap, to save users on 3×-plus devices a lot of bytes,

- send static, high-res, monochrome images to printers and e-ink devices.

Sky’s the limit, really.

Combining source and srcset

Because <source> also uses the srcset syntax, they can be combined. This means that you can still reap the performance benefits of srcset even while swapping out visually-different images with <source>. It gets pretty verbose though!

<picture>

<source

srcset="

baby-zoomed-out-2x.jpg 2x,

baby-zoomed-out.jpg

"

media="(min-width: 1000px)"

/>

<source

srcset="

baby-2x.jpg 2x,

baby.jpg

"

media="(min-width: 600px)"

/>

<img

srcset="

baby-zoomed-out-2x.jpg 2x

"

src="baby-zoomed-out.jpg"

alt="Baby Sleeping"

/>

</picture>The more variations you create and the more resized versions you create per variation, the more verbose this code has to get.

Fallbacks for modern image formats

The <picture> element is uniquely suited to being able to handle “fallbacks.” That is, images in cutting-edge formats that not all browsers might be able to handle, with alternative formats for browsers that can’t load the preferred, fancy one. For example, let’s say you want to use an image in the WebP format. It’s a pretty great image format, often being the most performant choice, and it’s supported everywhere that the <picture> element is, except Safari. You can handle that situation yourself, like:

<picture>

<source srcset="party.webp">

<img src="party.jpg" alt="A huge party with cakes.">

</picture>This succeeds in serving a WebP image to browsers that support it, and falls back to a JPEG image, which is definitely supported by all browsers.

Here’s an example of a photograph (of me) at the exact same size where the WebP version is about 10% (!!!) of the size of the JPEG.https://codepen.io/anon/embed/preview/BaoRxyP?height=450&theme-id=1&slug-hash=BaoRxyP&default-tab=result

How do you create a WebP image? Well, it’s more of a pain in the butt than you’d like it to be, that’s for sure. There are online converters, command line tools, and some modern design software, like Sketch, helps you export in that format. My preference is to use an image hosting CDN service that automatically sends images in the perfect format for the requesting browser, which makes all this unnecessary (because you can just use img/srcset).

WebP isn’t the only player like this. Safari doesn’t support WebP, but does support a format called JPG 2000 which has some advantages over JPEG. Internet Explorer 11 happens to support an image format called JPEG-XR which has different advantages. So to hit all three, that could look like:

<picture>

<source srcset="/images/cereal-box.webp" type="image/webp" />

<source srcset="/images/cereal-box.jp2" type="image/jp2" />

<img src="/images/cereal-box.jxr" type="image/vnd.ms-photo" />

</picture>This syntax (borrowed form a blog post by Josh Comeau) supports all three of the “next-gen” image formats in one go. IE 11 doesn’t support the <picture> syntax, but it doesn’t matter because it will get the <img> fallback which is in the JPEG-XR format it understands.

Estelle Weyl also covered this idea in a 2016 blog post on image optimization.

↩️ Back to top

Where do you get the differently-sized images?

You can make them yourself. Heck, even the free Preview app on my Mac can resize an image and “Save As.”

But that’s work. It’s more likely that the creation of variations of these images is automated somehow (see the section below) or you use a service that allows you to create variations just by manipulating the URL to the image. That’s a super common feature of any image hosting/image CDN service. To name a few:

- Cloudinary offers it

- Netlify offers it

- imgix offers it

- Image Optim offers it

- Filestack offers it

- Cloudflare offers it

Not only do these services offer on-the-fly image resizing, they also often offer additional stuff, like cropping, filtering, adding text, and all kinds of useful features, not to mention serving assets efficiently from a CDN and automatically in next-gen formats. That makes them a really strong choice for just about any website, I’d say.

Here’s Glen Maddern in a really great screencast talking about how useful Image CDNs can be:https://www.youtube.com/embed/_lQvw2vSDbs?feature=oembed

Design software is becoming more aware that we often need multiple copies of images. For example, the exporting interface from Figma is pretty nice, where any given selection can be exported. It allows multiple exports at once (in different sizes and formats) and remembers what you did the last time you exported.

Automated responsive images

The syntax of responsive images is complex to the point that doing it by hand is often out of the question. I’d highly recommend automating and abstracting as much of this away as possible. Fortunately, a lot of tooling that helps you build websites knows this and includes some sort of support for it. I think that’s great because that’s what software should be doing for us, particularly when it is something that is entirely programmatic and can be done better by code than by humans. Here are some examples…

- Cloudinary has this responsive breakpoints tool including an API for generating the perfect breakpoints.

- WordPress generates multiple versions of images and outputs in the responsive images syntax by default.

- Gatsby has a grab-bag of plugins for transforming and implementing images on your site. You ultimately implement them with gatsby-image, which is a whole fancy thing for implementing responsive images and other image loading optimizations. Speaking of React, it has component abstractions like “An Almost Ideal React Image Component” that also does cool stuff.

- Nicolas Hoizey’s Images Responsiver Node module (and it’s Eleventy plugin) makes a ton of smart markup choices for you, and pairs nicely with a CDN that can handle the on-the-fly resizing bits.

- These are just a few examples! Literally anything you can do to make this process easier or automatic is worth doing.

srcset with a healthy amount of pre-generated size options and a sizes attribute tailored to this theme.

I’m sure there are many more CMSs and other software products that help automate away the complexities of creating the responsive images syntax. While I love that all this syntax exists, I find it all entirely too cumbersome to author by hand. Still, I think it’s worth knowing all this syntax so that we can build our own abstractions, or check in on the abstractions we’re using to make sure they are doing things correctly.

Related concepts

- The

object-fitproperty in CSS controls how an image will behave in its own box. For example, an image will normally “squish” if you change the dimensions to something different than its natural aspect ratio, butobject-fitcan be used to crop it or contain it instead. - The

object-positionproperty in CSS allows you to nudge an image around within its box.

What about responsive images in CSS with background images?

We’ve covered exactly this before. The trick is to use @media queries to change the background-image source. For example:

.img {

background-image: url(small.jpg);

}

@media

(min-width: 468px),

(-webkit-min-device-pixel-ratio: 2),

(min-resolution: 192dpi) {

.img {

background-image: url(large.jpg);

}

}With this CSS syntax, depending on the browser conditions, the browser will only download one of the two images, which achieves the same performance goal that the responsive images syntax in HTML does. If it helps, think of the above as the CSS equivalent of the <picture> syntax: the browser must follow your rules and display what matches.

If you’re looking to let the browser choose the best option, like srcset/sizes, but in CSS, the solution is ultimately going to be the image-set() function. There’s two problems with image-set(), today, though:

- Support for it isn’t there yet. Safari’s implementation leads the pack, but

image-set()has been prefixed in Chrome for eight years, and it’s not there at all in Firefox. - Even the spec itself seems behind the times. For example, it only supports

xdescriptors (now, yet).

Best to just use media queries for now.

Do you need to polyfill?

I’m pretty meh on pollyfilling any of this right this moment. There is a great polyfill though, called Picturefill, which will buy you full IE 9-11 support if you need that. Remember, though, that none of this stuff breaks to the point of not displaying any image at all in non-supporting browsers, assuming you have an <img src="" alt=""> in there somewhere. If you make the (fairly safe) assumption that IE 11 is running on a low-pixel-density desktop display, you can make your image sources reflect that by default and build out from there.

Other important image considerations

- Optimizing quality: The point of responsive images is loading the smallest, most impactful resource that you can. You can’t achieve that without effectively compressing your image. You’re aiming for a “sweet spot” for every image, between looking good and being light. I like to let image hosting services solve this problem for me, but Etsy has a really great writeup of what they’ve been able to accomplish with infrastructure that they built themselves.

- Serving from CDNs: Speaking of image hosting services, speed comes in many forms. Fast servers that are geographically close to the user are an important speed factor as well.

- Caching: What’s better than loading less data over the network? Loading no data at all! That’s what HTTP caching is for. Using the

Cache-Controlheader, you can tell the browser to hang on to images so that if the same image is needed again, the browser doesn’t have to go over the network to get it, which is a massive performance boost for repeat viewings. - Lazy loading: This is another way to avoid loading images entirely. Lazy loading means waiting to download an image until it is in or near the viewport. So, for example, an image way far down the page won’t load if the user never scrolls there.

Conclusion

Let us know your thoughts in the comment section below.

Check out other publications to gain access to more digital resources if you are just starting out with Flux Resource.

Also contact us today to optimize your business(s)/Brand(s) for Search Engines